Introduction

Choosing the right diet is one of the most important decisions you make every day. With shelves full of packaged options and a growing body of nutrition research, understanding the difference between natural (whole) foods and processed foods helps you protect long-term health, manage weight, and support energy, skin, and mental well-being. This guide explains the definitions, health evidence, practical choices, and an actionable plan to balance convenience and nutrition so you can choose a diet that fits your body, budget, and lifestyle.

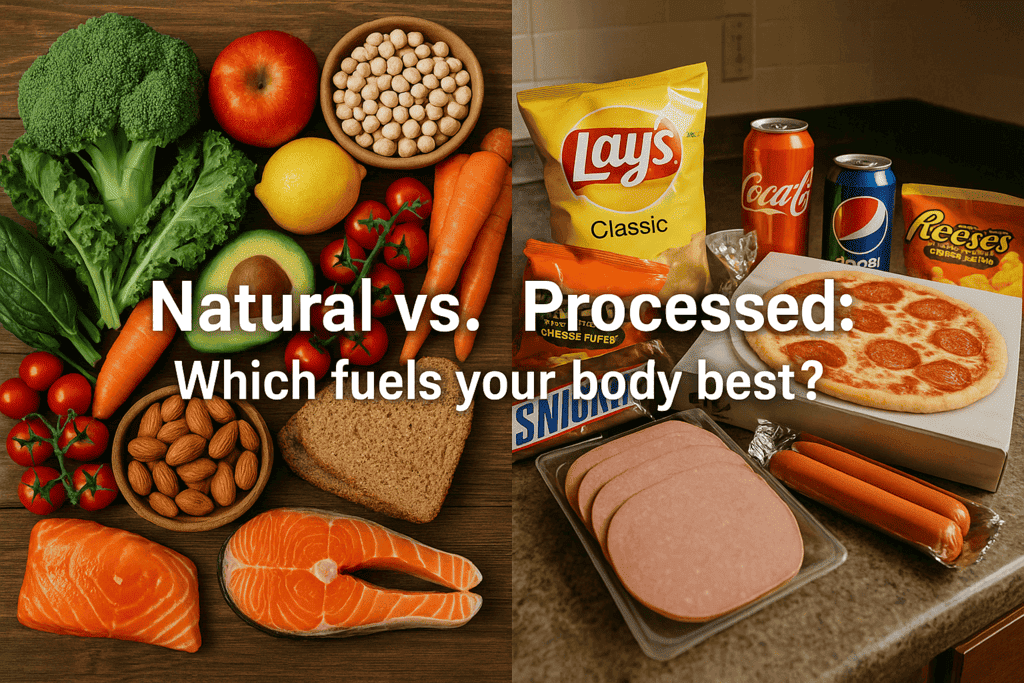

What we mean by natural and processed foods

- Natural / Whole foods — Foods that are minimally altered from their original state and contain few or no added ingredients (for example: fresh fruits, vegetables, whole grains, legumes, nuts, seeds, fresh fish, and unprocessed meats).

- Processed foods — Any food altered from its original form for convenience, safety, or shelf life (examples range from canned beans and frozen vegetables to packaged snacks and ready meals).

- Ultra-processed foods (UPFs) — Industrial formulations with multiple ingredients, additives, flavorings, and long ingredient lists (examples: sugary breakfast cereals, many ready-to-eat meals, packaged snacks, and soft drinks).

These definitions are widely used in nutrition science and public health guidance; the NOVA framework is a common classification for the level of processing. Wikipédia+1

Why the distinction matters : recent scientific evidence

- Several large cohort studies and meta-analyses link higher intake of ultra-processed foods with increased risks of obesity, type 2 diabetes, cardiovascular disease, some cancers, mental-health issues, and higher overall mortality. These associations persist across studies from Europe, North America, and Asia, suggesting a consistent global pattern. BMJ+1

- Randomized experimental work shows that diets high in ultra-processed foods lead to greater calorie intake and weight gain than matched whole-food diets, even when calories and macronutrients are controlled—pointing to mechanisms like ease of overconsumption, palatability, and reduced satiety. PubMed

- Large prospective cohorts (for example, the NutriNet-Santé study and later pooled analyses) reported associations between increasing UPF proportion of diet and higher risk of cardiovascular events, cancer incidence, and all-cause mortality. While observational studies cannot prove causation on their own, the convergence of cohort, meta-analytic, and randomized trial evidence strengthens concern about excessive UPF consumption. PubMed+1

- Global public-health agencies recommend limiting added sugars, industrial trans-fats, excess sodium, and ultra-processed products—favoring diets centered on whole foods and minimally processed staples. Organisation mondiale de la santé

(These are among the most important load-bearing statements in this guide; see references at the end for full citations.)

Key points (quick summary)

- Eat more whole foods: fruits, vegetables, whole grains, legumes, nuts, seeds, lean proteins, and oily fish.

- Limit ultra-processed foods: sugary drinks, packaged snacks, many ready meals, and processed meats.

- Read labels: fewer ingredients and recognizable names usually indicate less processing.

- Balance practicality and health: some processed foods (frozen vegetables, canned beans, plain yogurt) are healthy and useful.

- Focus on pattern, not perfection: prioritize whole foods most of the time; accept convenient choices when needed.

A clear table : Natural vs. Processed — fast comparison

| Feature | Natural / Whole Foods | Processed (including UPFs) |

|---|---|---|

| Typical ingredient list | Single ingredient or few ingredients | Long ingredient lists; additives, emulsifiers, preservatives |

| Nutrient density | Generally high (fiber, vitamins, minerals) | Often lower nutrient density; higher added sugar, sodium, saturated fat |

| Satiety effect | Higher — slows digestion, more chewing | Often lower — engineered for palatability, may encourage overeating |

| Convenience | May require preparation | Ready-to-eat; long shelf life |

| Cost (varies) | Can be inexpensive (beans, oats) or costly | Often inexpensive per calorie but low nutrition |

| Health associations | Linked to lower chronic disease risk | Linked to obesity, diabetes, CVD, some cancers, higher mortality in many studies. BMJ+1 |

Practical, evidence-based rules to choose the right diet for your body

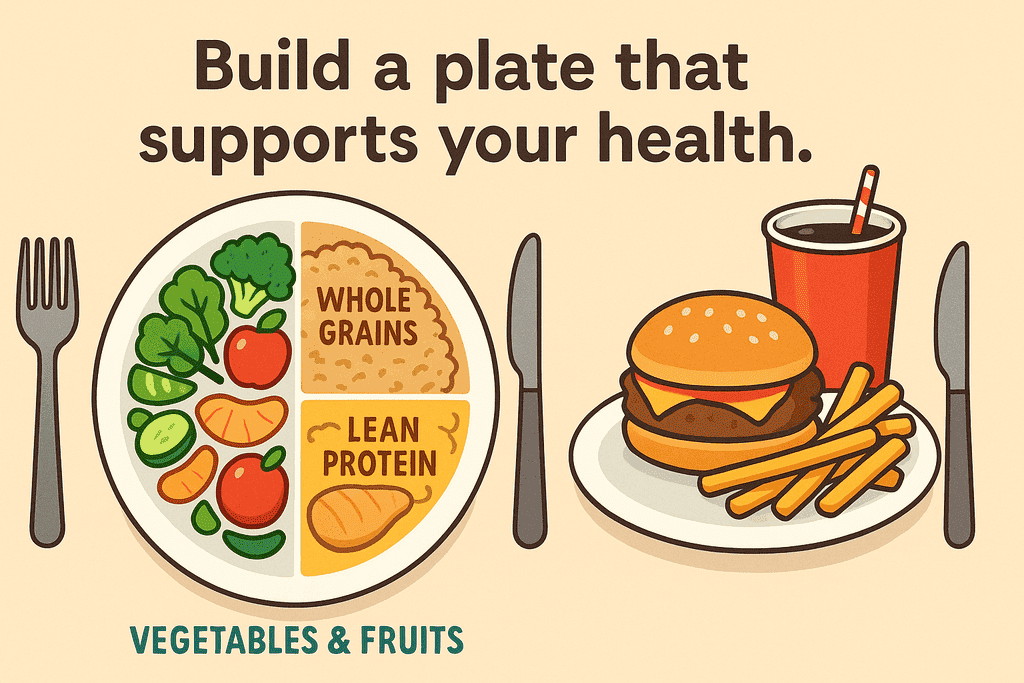

- Start with the plate: make at least half your plate vegetables and fruits at most meals. Whole plant foods supply fiber, micronutrients, and phytochemicals that support digestion, skin, immunity, and long-term health. (WHO healthy diet guidance supports this pattern.) Organisation mondiale de la santé

- Prioritize whole grains and legumes over refined grains and sugary breakfast products. Whole grains and legumes are linked to lower cardiometabolic risk and support steady blood sugar. The Nutrition Source

- Choose minimally processed convenience options when needed: frozen vegetables, canned tomatoes (no salt/sugar added), plain frozen fruit, canned fish in water, and plain yogurt are nutrient-dense and affordable. These can bridge time, budget, and cooking-skill gaps. nhs.uk

- Limit added sugar, sodium, and processed meats. Many cohort studies flag sugary beverages and processed meats as especially harmful among UPFs. Swap sugary drinks for water, unsweetened tea, or sparkling water with fruit. Harvard Chan School+1

- Use label literacy: watch for long lists of unrecognizable additives, phosphate salts, “hydrogenated” or “partially hydrogenated” fats, high fructose corn syrup, and multiple sources of added sugar. Shorter, readable ingredient lists usually indicate simpler processing.

- Be mindful of portion and context: some processed foods are fine in moderation; the problem is frequency and proportion. Substituting a home-made or minimally processed alternative most days yields measurable benefits.

- Individualize for health conditions: people with metabolic disease, hypertension, or specific nutrient needs may need stricter limits on sodium, refined carbs, or added sugars. Consult a healthcare professional for tailored guidance.

Practical meal plan examples (simple swaps)

- Breakfast: Swap a sugary cereal + milk for oat porridge with fruit, nuts, and yogurt.

- Lunch: Replace a microwaved ready meal with a grain bowl (brown rice or quinoa), roasted vegetables, canned chickpeas, and a drizzle of olive oil.

- Snack: Choose fresh fruit, nuts, or plain yogurt instead of packaged chips or cookies.

- Dinner: Use frozen fish fillet + steamed frozen vegetables + whole grain — fast, affordable, and nutrient-dense.

Figure: How to measure UPF exposure in your diet (simple checklist)

- What percentage of your daily calories comes from packaged ready-to-eat items?

- How many meals per week rely on ready meals, instant noodles, fast food, or packaged snacks?

- How many times per day do you consume sugar-sweetened beverages or processed meat products?

If your answers indicate high reliance (>30–40% of calories, multiple ready meals per week, daily sugary drinks), evidence suggests higher long-term risk and room for improvement. BMJ+1

Addressing common questions and myths

“All processed foods are unhealthy.”

Not true. Processing covers a huge range: freezing, drying, canning, pasteurizing, or milling can preserve nutrients and increase safety. The problem mostly concerns ultra-processed items designed for long shelf life and enhanced palatability. nhs.uk+1

“Natural foods are always affordable.”

Some whole foods are inexpensive (beans, oats, root vegetables), while others (fresh fish, organic produce) can be costlier. Strategic shopping (seasonal produce, frozen vegetables, bulk grains) helps keep whole-food diets affordable.

“A little processed food won’t hurt.”

Moderation matters. The studies show graded relationships — higher UPF proportion correlates with higher risk, so reducing the share of UPFs in your diet is beneficial. BMJ+1

Conclusion — A balanced, sustainable approach

Choosing the right diet for your body means adopting a pattern that emphasizes whole, minimally processed foods while recognizing real-world constraints. Scientific evidence from major cohort studies, randomized trials, and public-health agencies warns about the health risks associated with high consumption of ultra-processed foods, including higher rates of obesity, cardiometabolic disease, and mortality. But practical, affordable strategies — frozen or canned minimally processed options, whole grains, legumes, and simple cooking techniques — make it realistic to shift toward a more nourishing pattern.

Use label literacy, choose whole foods most of the time, keep processed convenience foods as occasional choices, and tailor recommendations to your personal health needs. Small, consistent dietary changes add up: swap one ultra-processed item for a whole-food alternative each week, and you will likely experience measurable benefits in weight, energy, mood, and long-term disease risk.

References (selected recent studies, agencies, and summaries)

- Srour B., et al. Ultra-processed food consumption and risk of type 2 diabetes in the NutriNet-Santé cohort. (Prospective study). PubMed. PubMed

- Lane M.M., et al. Ultra-processed foods and adverse health outcomes: umbrella review and meta-analysis. BMJ / Related analyses. BMJ

- Liang S., et al. Ultra-processed food and risk of all-cause mortality: meta-analysis (2025). PMC article. PMC

- Harvard T.H. Chan School of Public Health. Processed foods and health summary (The Nutrition Source, Harvard). The Nutrition Source+1

- World Health Organization. Healthy diet fact sheet. WHO guidance on fats, sugars, sodium and healthy diet patterns. Organisation mondiale de la santé

- Trumbo P.R., et al. Toward a science-based classification of processed foods (review on processing classification). PMC. PMC

- Hamano S., et al. Randomized trial: ultra-processed diets cause weight gain and increased energy intake. Diabetes Obes Metab. 2024. PubMed

- Torres-Collado L., et al. High consumption of ultra-processed foods associated with higher cancer risk. ScienceDirect (2024). ScienceDirect

- Wikipedia — Food processing / Ultra-processed food (overview and definitions). Wikipédia+1